Back in 2021, Miller’s marine team published an article discussing the impacts of the revised Maritime Traffic Safety Law of the People’s Republic of China, and the Chinese advances into the South China sea that followed suit. Applying a 2023 lens, we note how applicable and important this information is for markets and clients and provide updated commentary on the matter.

Over the last two years, the global political landscape has changed considerably, and the threat this law posed two years ago is now more relevant than ever. The insurance industry is acutely aware of the increased tension between China and Taiwan, ever since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine led to significant losses in shipping and aviation industries. A recent example of this is Lloyd’s asking its members to review realistic disaster scenarios (RDS) related to conflict in Taiwan for marine, aviation, and political risk markets.

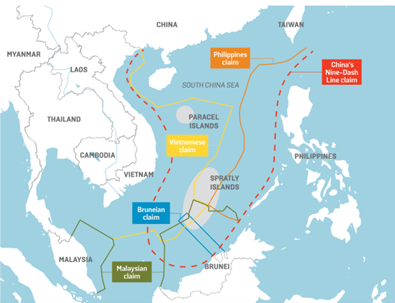

There has also been hostilities between China and Philippines over Spratly Island, with the US coming out with criticism over China’s handling of dispute as was recently pointed out by the article in gCaptain.

So what is the Maritime Traffic Safety Law of the People’s Republic of China (MTSL)?

MTSL is the primary law regulating maritime traffic safety in the sea areas within the jurisdiction of the People’s Republic of China, and monitors navigating, berthing, operations, and other activities relevant to maritime traffic safety. A revised version came into effect from 1 September 2021, with significant changes and new requirements being placed on shipowners.

What changed in the 2021 revision?

The MTSL was revised to include legal system amends, breach penalty increases, and requirements for shipowners to report certain types of foreign vessels. Since then, foreign vessels have been required to submit to Chinese supervision in ‘Chinese territorial waters’. Supposed vessels that “endanger the maritime traffic safety of China” have also been required to report their name, call sign, position, next port of call, and estimated time of arrival, as well as cargo reports to Chinese authorities.

What kind of vessels were, and continue to be affected?

The law applies to submersibles, nuclear vessels, ships carrying radioactive materials, bulk oil, chemicals, liquefied gas, and other toxic or harmful substances. In addition, vessels whose length, width, and height are close to the limits prescribed in the navigation conditions are affected, as well as the blanket wording of all "vessels that may endanger China's maritime traffic safety".

Where does responsibility now lie?

The MTSL cites elements of factors such as vessel safety, crew, traffic, maritime property, marine ecology instability, and environmental protection as reason for the harsh terms. Although cover for such areas can easily be obtained by the ISM and various other maritime standards, MTSL language implies that the Chinese state is taking on all these areas. Therefore, we should consider whether the onus was, and is still on the state to manage the responsibility of maritime safety.

The below wordings articulate the responsibilities self-declared by the state:

Article 21: “The State shall establish and improve the vessel positioning, navigation, timing, communication, remote monitoring and other maritime traffic support service systems to provide information services for vessels and offshore installations.”

Article 23: “The transport department under the State Council shall take necessary measures to ensure the rational layout and effective coverage of radio communication facilities for maritime traffic safety, plan the construction layout and sites of maritime radio stations in its system (industry), and verify and issue standard radio station licenses and radio station identification codes of vessels. The transport department under the State Council shall organize the construction of the maritime radio monitoring system in its system (industry) and monitor its radio signals and maintain the order of maritime radio waves in conjunction with the radio regulatory authority of the state.”

Ultimately, the line is blurred, but this calls into question whether China continues to dictate its own maritime standards, and subsequently imposes those on others.

What comes under ‘Chinese territorial waters’?

The South China sea is still heavily disputed for control. The Chinese state continues to claim it as its sovereign territory under the ‘Nine-Dash line’, however the US-backed neighbouring territories would beg to differ. The below diagram displays the various claims along the Nine-Dash line.

How does this continue to compare against current laws governing territorial waters?

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) territorial sea definition refers heavily to nautical mile markers. The territorial sea is regarded as the sovereign territory of the state and accordingly, the state has the right to implement territorial rights up to 12 nautical miles into the sea. The UNCLOS also states that all vessels have the right of “innocent passage” through this region.

In 2021, the updates to the MTSL contradicted the UNCLOS definition, and to date China has yet to define what they consider to be ‘Chinese territorial waters’. Also remaining undefined to date are the ways in which China plan to enforce their law in territories that conflict with UNCLOS.

We suggest that vessels continue to exercise caution when passing through the South China sea and ensure that all documentation is up to date, especially when calling at a Chinese port.

Does the MTSL impact shipping in today’s climate?

Yes, definitely. All maritime traffic, trading or passing within the nine-dash line is vulnerable to Chinese actions, especially if it is under the disguise of safety law like MTSL. Vessels within a strait or channel are especially susceptible to Chinese authorities, for example, an innocent vessel crossing the Taiwan strait, which is about 220 nautical miles (410 km) at its widest and 70 nautical miles (130 km) at its narrowest points, would likely be intercepted due to the narrow size.

Even after accounting for China and Taiwan’s territorial waters respectively, there is a wide strip of water available to freely navigate, in line with the UNCLOS. Any political or military move by China into Taiwan could lead to possible detention of ships by PRC under the auspice MTSL.

How can Miller help?

For vessels within designated territorial waters as defined by UNCLOS, the situation is clear that shipowners entering those waters will be required to submit to Chinese supervision. The major uncertainty for shipowners and charterers at this stage surrounds detention following a breach of the new legislation within disputed waters not recognised by non-Chinese governments and that lie beyond the UNCLOS defined territorial waters.

Miller’s marine team has worked with the market to provide an insurance solution to help alleviate this uncertainty and to provide some coverage following the imposition of the Maritime Traffic Safety Law by the People’s Republic of China. The coverage would respond for vessels transiting outside Chinese UNCLOS territorial waters and would provide indemnity for otherwise unrecoverable loss of hire following detention/detainment. The coverage negotiated with insurers is primary with nil deductible and so would respond from day one following detention/detainment and protect freight earnings and business interruption.

Miller would be delighted to discuss the product in more detail at owner's or charterer's request.